Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

Published on October 14, 2022 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Tegan George.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your paper or dissertation topic is relevant and grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualizes your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis , or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarize yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalizations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyze The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviorist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarizing and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organize by theory cluster

- Organize by date

It’s important that the information in your theoretical framework is clear for your reader. Make sure to ask a friend to read this section for you, or use a professional proofreading service .

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis , or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing. Scribbr. Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Theoretical Framework

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Theories are formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounded assumptions or predictions of behavior. The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical framework encompasses not just the theory, but the narrative explanation about how the researcher engages in using the theory and its underlying assumptions to investigate the research problem. It is the structure of your paper that summarizes concepts, ideas, and theories derived from prior research studies and which was synthesized in order to form a conceptual basis for your analysis and interpretation of meaning found within your research.

Abend, Gabriel. "The Meaning of Theory." Sociological Theory 26 (June 2008): 173–199; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (December 2018): 44-53; Swanson, Richard A. Theory Building in Applied Disciplines . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2013; Varpio, Lara, Elise Paradis, Sebastian Uijtdehaage, and Meredith Young. "The Distinctions between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework." Academic Medicine 95 (July 2020): 989-994.

Importance of Theory and a Theoretical Framework

Theories can be unfamiliar to the beginning researcher because they are rarely applied in high school social studies curriculum and, as a result, can come across as unfamiliar and imprecise when first introduced as part of a writing assignment. However, in their most simplified form, a theory is simply a set of assumptions or predictions about something you think will happen based on existing evidence and that can be tested to see if those outcomes turn out to be true. Of course, it is slightly more deliberate than that, therefore, summarized from Kivunja (2018, p. 46), here are the essential characteristics of a theory.

- It is logical and coherent

- It has clear definitions of terms or variables, and has boundary conditions [i.e., it is not an open-ended statement]

- It has a domain where it applies

- It has clearly described relationships among variables

- It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions

- It comprises of concepts, themes, principles, and constructs

- It must have been based on empirical data [i.e., it is not a guess]

- It must have made claims that are subject to testing, been tested and verified

- It must be clear and concise

- Its assertions or predictions must be different and better than those in existing theories

- Its predictions must be general enough to be applicable to and understood within multiple contexts

- Its assertions or predictions are relevant, and if applied as predicted, will result in the predicted outcome

- The assertions and predictions are not immutable, but subject to revision and improvement as researchers use the theory to make sense of phenomena

- Its concepts and principles explain what is going on and why

- Its concepts and principles are substantive enough to enable us to predict a future

Given these characteristics, a theory can best be understood as the foundation from which you investigate assumptions or predictions derived from previous studies about the research problem, but in a way that leads to new knowledge and understanding as well as, in some cases, discovering how to improve the relevance of the theory itself or to argue that the theory is outdated and a new theory needs to be formulated based on new evidence.

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. The theoretical framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research paper and that relate to the broader areas of knowledge being considered.

The theoretical framework is most often not something readily found within the literature . You must review course readings and pertinent research studies for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power.

The theoretical framework strengthens the study in the following ways :

- An explicit statement of theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically.

- The theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, you are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods.

- Articulating the theoretical assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to intellectually transition from simply describing a phenomenon you have observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon.

- Having a theory helps you identify the limits to those generalizations. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a phenomenon of interest and highlights the need to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances.

- The theoretical framework adds context around the theory itself based on how scholars had previously tested the theory in relation their overall research design [i.e., purpose of the study, methods of collecting data or information, methods of analysis, the time frame in which information is collected, study setting, and the methodological strategy used to conduct the research].

By virtue of its applicative nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges associated with a phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways.

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Corvellec, Hervé, ed. What is Theory?: Answers from the Social and Cultural Sciences . Stockholm: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2013; Asher, Herbert B. Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1984; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (2018): 44-53; Omodan, Bunmi Isaiah. "A Model for Selecting Theoretical Framework through Epistemology of Research Paradigms." African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2022): 275-285; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Jarvis, Peter. The Practitioner-Researcher. Developing Theory from Practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Strategies for Developing the Theoretical Framework

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research problem. Identify the assumptions from which the author(s) addressed the problem.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

Structure and Writing Style

The theoretical framework may be rooted in a specific theory , in which case, your work is expected to test the validity of that existing theory in relation to specific events, issues, or phenomena. Many social science research papers fit into this rubric. For example, Peripheral Realism Theory, which categorizes perceived differences among nation-states as those that give orders, those that obey, and those that rebel, could be used as a means for understanding conflicted relationships among countries in Africa. A test of this theory could be the following: Does Peripheral Realism Theory help explain intra-state actions, such as, the disputed split between southern and northern Sudan that led to the creation of two nations?

However, you may not always be asked by your professor to test a specific theory in your paper, but to develop your own framework from which your analysis of the research problem is derived . Based upon the above example, it is perhaps easiest to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as an answer to two basic questions:

- What is the research problem/question? [e.g., "How should the individual and the state relate during periods of conflict?"]

- Why is your approach a feasible solution? [i.e., justify the application of your choice of a particular theory and explain why alternative constructs were rejected. I could choose instead to test Instrumentalist or Circumstantialists models developed among ethnic conflict theorists that rely upon socio-economic-political factors to explain individual-state relations and to apply this theoretical model to periods of war between nations].

The answers to these questions come from a thorough review of the literature and your course readings [summarized and analyzed in the next section of your paper] and the gaps in the research that emerge from the review process. With this in mind, a complete theoretical framework will likely not emerge until after you have completed a thorough review of the literature .

Just as a research problem in your paper requires contextualization and background information, a theory requires a framework for understanding its application to the topic being investigated. When writing and revising this part of your research paper, keep in mind the following:

- Clearly describe the framework, concepts, models, or specific theories that underpin your study . This includes noting who the key theorists are in the field who have conducted research on the problem you are investigating and, when necessary, the historical context that supports the formulation of that theory. This latter element is particularly important if the theory is relatively unknown or it is borrowed from another discipline.

- Position your theoretical framework within a broader context of related frameworks, concepts, models, or theories . As noted in the example above, there will likely be several concepts, theories, or models that can be used to help develop a framework for understanding the research problem. Therefore, note why the theory you've chosen is the appropriate one.

- The present tense is used when writing about theory. Although the past tense can be used to describe the history of a theory or the role of key theorists, the construction of your theoretical framework is happening now.

- You should make your theoretical assumptions as explicit as possible . Later, your discussion of methodology should be linked back to this theoretical framework.

- Don’t just take what the theory says as a given! Reality is never accurately represented in such a simplistic way; if you imply that it can be, you fundamentally distort a reader's ability to understand the findings that emerge. Given this, always note the limitations of the theoretical framework you've chosen [i.e., what parts of the research problem require further investigation because the theory inadequately explains a certain phenomena].

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Conceptual Framework: What Do You Think is Going On? College of Engineering. University of Michigan; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Lynham, Susan A. “The General Method of Theory-Building Research in Applied Disciplines.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 4 (August 2002): 221-241; Tavallaei, Mehdi and Mansor Abu Talib. "A General Perspective on the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research." Journal of International Social Research 3 (Spring 2010); Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Weick, Karl E. “The Work of Theorizing.” In Theorizing in Social Science: The Context of Discovery . Richard Swedberg, editor. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), pp. 177-194.

Writing Tip

Borrowing Theoretical Constructs from Other Disciplines

An increasingly important trend in the social and behavioral sciences is to think about and attempt to understand research problems from an interdisciplinary perspective. One way to do this is to not rely exclusively on the theories developed within your particular discipline, but to think about how an issue might be informed by theories developed in other disciplines. For example, if you are a political science student studying the rhetorical strategies used by female incumbents in state legislature campaigns, theories about the use of language could be derived, not only from political science, but linguistics, communication studies, philosophy, psychology, and, in this particular case, feminist studies. Building theoretical frameworks based on the postulates and hypotheses developed in other disciplinary contexts can be both enlightening and an effective way to be more engaged in the research topic.

CohenMiller, A. S. and P. Elizabeth Pate. "A Model for Developing Interdisciplinary Research Theoretical Frameworks." The Qualitative Researcher 24 (2019): 1211-1226; Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Undertheorize!

Do not leave the theory hanging out there in the introduction never to be mentioned again. Undertheorizing weakens your paper. The theoretical framework you describe should guide your study throughout the paper. Be sure to always connect theory to the review of pertinent literature and to explain in the discussion part of your paper how the theoretical framework you chose supports analysis of the research problem or, if appropriate, how the theoretical framework was found to be inadequate in explaining the phenomenon you were investigating. In that case, don't be afraid to propose your own theory based on your findings.

Yet Another Writing Tip

What's a Theory? What's a Hypothesis?

The terms theory and hypothesis are often used interchangeably in newspapers and popular magazines and in non-academic settings. However, the difference between theory and hypothesis in scholarly research is important, particularly when using an experimental design. A theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. Theories arise from repeated observation and testing and incorporates facts, laws, predictions, and tested assumptions that are widely accepted [e.g., rational choice theory; grounded theory; critical race theory].

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. For example, an experiment designed to look at the relationship between study habits and test anxiety might have a hypothesis that states, "We predict that students with better study habits will suffer less test anxiety." Unless your study is exploratory in nature, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen during the course of your research.

The key distinctions are:

- A theory predicts events in a broad, general context; a hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a specified set of circumstances.

- A theory has been extensively tested and is generally accepted among a set of scholars; a hypothesis is a speculative guess that has yet to be tested.

Cherry, Kendra. Introduction to Research Methods: Theory and Hypothesis. About.com Psychology; Gezae, Michael et al. Welcome Presentation on Hypothesis. Slideshare presentation.

Still Yet Another Writing Tip

Be Prepared to Challenge the Validity of an Existing Theory

Theories are meant to be tested and their underlying assumptions challenged; they are not rigid or intransigent, but are meant to set forth general principles for explaining phenomena or predicting outcomes. Given this, testing theoretical assumptions is an important way that knowledge in any discipline develops and grows. If you're asked to apply an existing theory to a research problem, the analysis will likely include the expectation by your professor that you should offer modifications to the theory based on your research findings.

Indications that theoretical assumptions may need to be modified can include the following:

- Your findings suggest that the theory does not explain or account for current conditions or circumstances or the passage of time,

- The study reveals a finding that is incompatible with what the theory attempts to explain or predict, or

- Your analysis reveals that the theory overly generalizes behaviors or actions without taking into consideration specific factors revealed from your analysis [e.g., factors related to culture, nationality, history, gender, ethnicity, age, geographic location, legal norms or customs , religion, social class, socioeconomic status, etc.].

Philipsen, Kristian. "Theory Building: Using Abductive Search Strategies." In Collaborative Research Design: Working with Business for Meaningful Findings . Per Vagn Freytag and Louise Young, editors. (Singapore: Springer Nature, 2018), pp. 45-71; Shepherd, Dean A. and Roy Suddaby. "Theory Building: A Review and Integration." Journal of Management 43 (2017): 59-86.

- << Previous: The Research Problem/Question

- Next: 5. The Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 1:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

Published on 8 July 2022 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Your theoretical framework defines the key concepts in your research, suggests relationships between them, and discusses relevant theories based on your literature review .

A strong theoretical framework gives your research direction, allowing you to convincingly interpret, explain, and generalise from your findings.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Sample problem statement and research questions, sample theoretical framework, your theoretical framework, frequently asked questions about sample theoretical frameworks.

Your theoretical framework is based on:

- Your problem statement

- Your research questions

- Your literature review

To investigate this problem, you have zeroed in on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

- Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

- Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

- Research question : How can the satisfaction of the boutique’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

The concepts of ‘customer loyalty’ and ‘customer satisfaction’ are clearly central to this study, along with their relationship to the likelihood that a customer will return. Your theoretical framework should define these concepts and discuss theories about the relationship between these variables.

Some sub-questions could include:

- What is the relationship between customer loyalty and customer satisfaction?

- How satisfied and loyal are the boutique’s online customers currently?

- What factors affect the satisfaction and loyalty of the boutique’s online customers?

As the concepts of ‘loyalty’ and ‘customer satisfaction’ play a major role in the investigation and will later be measured, they are essential concepts to define within your theoretical framework .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Below is a simplified example showing how you can describe and compare theories. In this example, we focus on the concept of customer satisfaction introduced above.

Customer satisfaction

Thomassen (2003, p. 69) defines customer satisfaction as ‘the perception of the customer as a result of consciously or unconsciously comparing their experiences with their expectations’. Kotler and Keller (2008, p. 80) build on this definition, stating that customer satisfaction is determined by ‘the degree to which someone is happy or disappointed with the observed performance of a product in relation to his or her expectations’.

Performance that is below expectations leads to a dissatisfied customer, while performance that satisfies expectations produces satisfied customers (Kotler & Keller, 2003, p. 80).

The definition of Zeithaml and Bitner (2003, p. 86) is slightly different from that of Thomassen. They posit that ‘satisfaction is the consumer fulfillment response. It is a judgement that a product or service feature, or the product of service itself, provides a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment.’ Zeithaml and Bitner’s emphasis is thus on obtaining a certain satisfaction in relation to purchasing.

Thomassen’s definition is the most relevant to the aims of this study, given the emphasis it places on unconscious perception. Although Zeithaml and Bitner, like Thomassen, say that customer satisfaction is a reaction to the experience gained, there is no distinction between conscious and unconscious comparisons in their definition.

The boutique claims in its mission statement that it wants to sell not only a product, but also a feeling. As a result, unconscious comparison will play an important role in the satisfaction of its customers. Thomassen’s definition is therefore more relevant.

Thomassen’s Customer Satisfaction Model

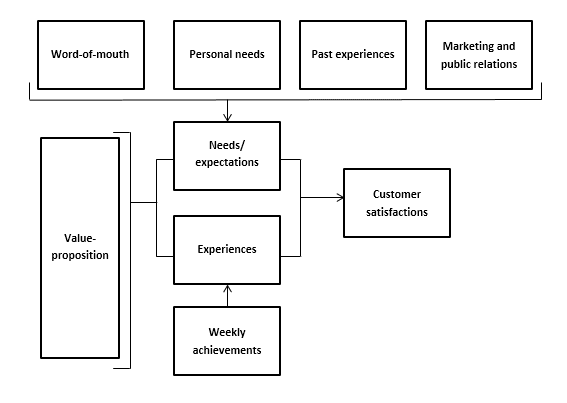

According to Thomassen, both the so-called ‘value proposition’ and other influences have an impact on final customer satisfaction. In his satisfaction model (Fig. 1), Thomassen shows that word-of-mouth, personal needs, past experiences, and marketing and public relations determine customers’ needs and expectations.

These factors are compared to their experiences, with the interplay between expectations and experiences determining a customer’s satisfaction level. Thomassen’s model is important for this study as it allows us to determine both the extent to which the boutique’s customers are satisfied, as well as where improvements can be made.

Figure 1 Customer satisfaction creation

Of course, you could analyse the concepts more thoroughly and compare additional definitions to each other. You could also discuss the theories and ideas of key authors in greater detail and provide several models to illustrate different concepts.

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Vinz, S. (2022, October 10). Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis. Scribbr. Retrieved 8 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/example-theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, dissertation & thesis outline | example & free templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Building and Using Theoretical Frameworks

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 December 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- James Hiebert 6 ,

- Jinfa Cai 7 ,

- Stephen Hwang 7 ,

- Anne K Morris 6 &

- Charles Hohensee 6

Part of the book series: Research in Mathematics Education ((RME))

14k Accesses

1 Citations

Theoretical frameworks can be confounding. They are supposed to be very important, but it is not always clear what they are or why you need them. Using ideas from Chaps. 1 and 2 , we describe them as local theories that are custom-designed for your study. Although they might use parts of larger well-known theories, they are created by individual researchers for particular studies. They are developed through the cyclic process of creating more precise and meaningful hypotheses. Building directly on constructs from the previous chapters, you can think of theoretical frameworks as equivalent to the most compelling, complete rationales you can develop for the predictions you make. Theoretical frameworks are important because they do lots of work for you. They incorporate the literature into your rationale, they explain why your study matters, they suggest how you can best test your predictions, and they help you interpret what you find. Your theoretical framework creates an essential coherence for your study and for the paper you are writing to report the study.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Part I. What Are Theoretical Frameworks?

As the name implies, a theoretical framework is a type of theory. We will define it as the custom-made theory that focuses specifically on the hypotheses you want to test and the research questions you want to answer. It is custom-made for your study because it explains why your predictions are plausible. It does no more and no less. Building directly on Chap. 2 , as you develop more complete rationales for your predictions, you are actually building a theory to support your predictions. Our goal in this chapter is for you to become comfortable with what theoretical frameworks are, with how they relate to the general concept of theory, with what role they play in scientific inquiry, and with why and how to create one for your study.

As you read this chapter, it will be helpful to remember that our definitions of terms in this book, such as theoretical framework, are based on our view of scientific inquiry as formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses. We define theoretical framework in ways that continue the coherent story we lay out across all phases of scientific inquiry and all the chapters this book. You are likely to find descriptions of theoretical frameworks in other sources that differ in some ways from our description. In addition, you are likely to see other terms that we would include as synonyms for theoretical framework, including conceptual framework. We suggest that when you encounter these special terms, make sure you understand how the authors are defining them.

Definitions of Theories

We begin by stepping back and considering how theoretical frameworks fit within the concept of theory, as usually defined. There are many definitions of theory; you can find a huge number simply by googling “theory.” Educational researchers and theorists often propose their own definitions but many of these are quite similar. Praetorius and Charalambous ( 2022 ) reviewed a number of definitions to set the stage for examining theories of teaching. Here are a few, beginning with a dictionary definition:

Lexico.com Dictionary (Oxford University Press, 2021 ): “A supposition or a system of ideas intended to explain something, especially one based on general principles independent of the thing to be explained.”

Biddle and Anderson ( 1986 ): “By scientific theory we mean the system of concepts and propositions that is used to represent, think about, and predict observable events. Within a mature science that theory is also explanatory and formalized. It does not represent ultimate ‘truth,’ however; indeed, it will be superseded by other theories presently. Instead, it represents the best explanation we have, at present, for those events we have so far observed” (p. 241).

Kerlinger ( 1964 ): “A theory is a set of interrelated constructs (concepts), definitions and propositions which presents a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relations among variables, with the purpose of explaining and predicting phenomena” (p. 11).

Colquitt and Zapata-Phelan ( 2007 ): The authors say that theories allow researchers to understand and predict outcomes of interest, describe and explain a process or sequence of events, raise consciousness about a specific set of concepts as well as prevent scholars from “being dazzled by the complexity of the empirical world by providing a linguistic tool for organizing it” (p. 1281).

For our purposes, it is important to notice two things that most definitions of theories share: They are descriptions of a connected set of facts and concepts, and they are created to predict and/or explain observed events. You can connect these ideas to Chaps. 1 and 2 by noticing that the language for the descriptors of scientific inquiry we suggested in Chap. 1 are reflected in the definitions of theories. In particular, notice in the definitions two of the descriptors: “Observing something and trying to explain why it is the way it is” and “Updating everyone’s thinking in response to more and better information.” Notice also in the definitions the emphasis on the elements of a theory similar to the elements of a rationale described in Chap. 2 : definitions, variables, and mechanisms that explain relationships.

Exercise 3.1

Before you continue reading, in your own words, write down a definition for “theoretical framework.”

Theoretical Frameworks Are Local Theories

There are strong similarities between building theories and doing scientific inquiry (formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses). In both cases, the researcher (or theorist) develops explanations for phenomena of interest. Building theories involves describing the concepts and conjectures that predict and later explain the events, and specifying the predictions by identifying the variables that will be measured. Doing scientific inquiry involves many of the same activities: formulating predictions for answers to questions about the research problem and building rationales to explain why the predictions are appropriate and reasonable.

As you move through the cycles described in Chap. 2 —cycles of asking questions, making predictions, writing out the reasons for these predictions, imagining how you would test the predictions, reading more about what scholars know and have hypothesized, revising your predictions (and maybe your questions), and so on—your theoretical rationales will become both more complete and more precise. They will become more complete as you find new arguments and new data in the literature and through talking with others, and they will become sharper as you remove parts of the rationales that originally seemed relevant but now create mostly distractions and noise. They will become increasingly customized local theories that support your predictions.

In the end, your framework should be as clean and frugal as possible without missing arguments or data that are directly relevant. In the language of mathematics, you should use an idea if and only if it makes your framework stronger, more convincing. On the one hand, including more than you need becomes a distraction and can confuse both you, as you try to conceptualize and conduct your research, and others, as they read your reports of your research. On the other hand, including less than you need means your rationale is not yet as convincing as it could be.

The set of rationales, blended together, constitute a precisely targeted custom-made theory that supports your predictions. Custom designing your rationales for your specific predictions means you probably will be drawing ideas from lots of sources and combining them in new ways. You are likely to end up with a unique local theory, a theoretical framework that has not been proposed in exactly the same way before.

A common misconception among beginning researchers is that they should borrow a theoretical framework from somewhere else, especially from well-known scholars who have theories named after them or well-known general theories of learning or teaching. You are likely to use ideas from these theories (e.g., Vygotsky’s theory of learning, Maslow’s theory of motivation, constructivist theories of learning), but you will combine specific ideas from multiple sources to create your own framework. When someone asks, “What theoretical framework are you using?” you would not say, “A Vygotskian framework.” Rather, you would say something like, “I created my framework by combining ideas from different sources so it explains why I am making these predictions.”

You should think of your theoretical framework as a potential contribution to the field, all on its own. Although it is unique to your study, there are elements of your framework that other researchers could draw from to construct theoretical frameworks for their studies, just as you drew from others’ frameworks. In rare cases, other researchers could use your framework as is. This might happen if they want to replicate your study or extend it in very specific ways. Usually, however, researchers borrow parts of frameworks or modify them in ways that better fit their own studies. And, just as you are doing with your own theoretical framework, those researchers will need to justify why borrowing or modifying parts of your framework will help them explain the predictions they are making.

Considering your theoretical framework as a contribution to the field means you should treat it as a central part of scientific inquiry, not just as a required step that must be completed before moving to the next phase. To be useful, the theoretical framework should be constructed as a critical part of conceptualizing and carrying out the research (Cai et al., 2019c ). This also means you should write out your framework as you are developing it. This will be a key part of your evolving research paper. Because your framework will be adjusted multiple times, your written document will go through many drafts.

If you are a graduate student, do not think of the potential audience for your written framework as only your advisor and committee members. Rather, consider your audience to be the larger community of education researchers. You will need to be sure all the key terms are defined and each part of your argument is clear, even to those who are not familiar with your study. This is one place where writing out your framework can benefit your study—it is easy to assume key terms are clear, but then you find out they are not so clear, even to you, when trying to communicate them. Failing to notice this lack of clarity can create lots of problems down the road.

Exercise 3.2

Researchers have used a number of different metaphors to describe theoretical frameworks. Maxwell (2005) referred to a theoretical framework as a “coat closet” that provides “places to ‘hang’ data, showing their relationship to other data,” although he cautioned that “a theory that neatly organizes some data will leave other data disheveled and lying on the floor, with no place to put them” (p. 49). Lester (2005) referred to a framework as a “scaffold” (p. 458), and others have called it a “blueprint” (Grant & Osanloo, 2014). Eisenhart (1991) described the framework as a “skeletal structure of justification” (p. 209). Spangler and Williams (2019) drew an analogy to the role that a house frame provides in preventing the house from collapsing in on itself. What aspects of a theoretical framework does each of these metaphors capture? What aspects does each fail to capture? Which metaphor do you find best fits your definition of a theoretical framework? Why? Can you think of another metaphor to describe a theoretical framework?

Part II. Why Do You Need Theoretical Frameworks?

Theoretical frameworks do lots of work for you. They have four primary purposes. They ensure (1) you have sound reasons to expect your predictions will be accurate, (2) you will craft appropriate methods to test your predictions, (3) you can interpret appropriately what you find, and (4) your interpretations will contribute to the accumulation of a knowledge base that can improve education. How do they do this?

Supporting Your Predictions

In previous chapters and earlier in this chapter, we described how theoretical frameworks are built along with your predictions. In fact, the rationales you develop for convincing others (and yourself) that your predictions are accurate are used to refine your predictions, and vice versa. So, it is not surprising that your refined framework provides a rationale that is fully aligned with your predictions. In fact, you could think of your theoretical framework as your best explanation, at any given moment during scientific inquiry, for why you will find what you think you will find.

Throughout this book, we are using “explanation” in a broad sense. As we noted earlier, an explanation for why your predictions are accurate includes all the concepts and definitions about mechanisms (Kerlinger’s, 1964 definition of “theory”) that help you describe why you think the predictions you are making are the best predictions possible. The explanation also identifies and describes all the variables that make up your predictions, variables that will be measured to test your predictions.

Crafting Appropriate Methods

Critical decisions you make to test your hypotheses form the methods for your scientific inquiry. As we have noted, imagining how you will test your hypotheses helps you decide whether the empirical observations you make can be compared with your predictions or whether you need to revise the methods (or your predictions). Remember, the theoretical framework is the coherent argument built from the rationales you develop as part of each hypothesis you formulate. Because each rationale explains why you make that prediction, it contains helpful cues for which methods would provide the fairest and most complete test of that prediction. In fact, your theoretical framework provides a logic against which you can check every aspect of the methods you imagine using.

You might find it helpful to ask yourself two questions as you think about which methods are best aligned with your theoretical framework. One is, “After reading my theoretical framework, will anyone be surprised by the methods I use?” If so, you should look back at your framework and make sure the predictions are clear and the rationales include all the reasons for your predictions. Your framework should telegraph the methods that make the most sense. The other question is, “Are there some predictions for which I can’t imagine appropriate methods?” If so, we recommend you return to your hypotheses—to your predictions and rationales (theoretical framework)—to make sure the predictions are phrased as precisely as possible and your framework is fully developed. In most cases, this will help you imagine methods that could be used. If not, you might need to revise your hypotheses.

Exercise 3.3

Kerlinger ( 1964 ) stated, “A theory is a set of interrelated constructs (concepts), definitions and propositions which presents a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relations among variables, with the purpose of explaining and predicting phenomena” (p. 11). What role do definitions play in a theoretical framework and how do they help in crafting appropriate methods?

Exercise 3.4

Sarah is in the beginning stages of developing a study. Her initial prediction is: There is a relationship between pedagogical content knowledge and ambitious teaching. She realizes that in order to craft appropriate measures, she needs to develop definitions of these constructs. Sarah’s original definitions are: Pedagogical content knowledge is knowledge about subject matter that is relevant to teaching. Ambitious teaching is teaching that is responsive to students’ thinking and develops a deep knowledge of content. Sarah recognizes that her prediction and her definitions are too broad and too general to work with. She wants to refine the definitions so they can guide the refinement of her prediction and the design of the study. Develop definitions of these two constructs that have clearer implications for the design and that would help Sarah to refine her prediction. (tip: Sarah may need to reduce the scope of her prediction by choosing to focus only on one aspect of pedagogical content knowledge and one aspect of ambitious teaching. Then, she can more precisely define those aspects.)

Guiding Interpretations of the Data

By providing rationales for your predictions, your theoretical framework explains why you think your predictions will be accurate. In education, researchers almost always find that if they make specific predictions (which they should), the predictions are not entirely accurate. This is a consequence of the fact that theoretical frameworks are never complete. Recall the definition of theories from Biddle and Anderson ( 1986 ): A theory “does not represent ultimate ‘truth,’ however; indeed, it will be superseded by other theories presently. Instead, it represents the best explanation we have, at present, for those events we have so far observed” (p. 241). If you have created your best developed and clearly stated theoretical framework that explains why you expected certain results, you can focus your interpretation on the ways in which your theoretical framework should be revised.

Focusing on realigning your theoretical framework with the data you collected produces the richest interpretation of your results. And it prevents you from making one of the most common errors of beginning researchers (and veteran researchers, as well): claiming that your results say more than they really do. Without this anchor to ground your interpretation of the data, it is easy to overgeneralize and make claims that go beyond the evidence.

In one of the definitions of theory presented earlier, Colquitt and Zapata-Phelan ( 2007 ) say that theories prevent scholars from “being dazzled by the complexity of the empirical world” (p. 1281). Theoretical frameworks keep researchers grounded by setting parameters within which the empirical world can be interpreted.

Exercise 3.5

Find two published articles that explicitly present theoretical frameworks (not all articles do). Where do you see evidence of the researchers using their theoretical frameworks to inform, shape, and connect other parts of their articles?

Showing the Contribution of Your Study

Theoretical frameworks contain the arguments that define the contribution of research studies. They do this in two ways, by showing how your study extends what is known and by setting the parameters for your contribution.

Showing How Your Study Extends What Is Known

Because your theoretical framework is built from what is already known or has been proposed, it situates your study in work that has occurred before. A clearly written framework shows readers how your study will take advantage of what is known to extend it further. It reveals what is new about what you are studying. The predictions that are generated from your framework are predictions that have never been made in quite the same way. They predict you will find something that has not been found previously in exactly this way. Your theoretical framework allows others to see the contributions that your study is likely to make even before the study has been conducted.

Setting the Parameters for Your Contribution

Earlier we noted that theoretical frameworks keep researchers grounded by setting parameters within which they should interpret their data. They do this by providing an initial explanation for why researchers expect to find particular results. The explanation is custom-built for each study. This means it uniquely explains the expected results. The results will almost surely turn out somewhat differently than predicted. Interpreting the data includes revising the initial explanation. So, you will end up with two versions of your theoretical framework, one that explains what you expected to find plus a second, updated framework that explains what you actually found.

The two frameworks—the initial version and the updated version—define the parameters of your study’s contribution. The difference between the two frameworks is what can be learned from your study. The first framework is a claim about what is known before you conduct your study about the phenomenon you are studying; the updated framework is a claim about how what is known has changed based on your results. It is the new aspects of the updated framework that capture the important contribution of your work.

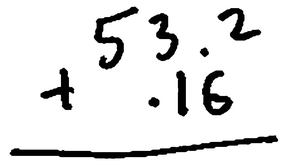

Here is a brief example. Suppose you study the errors fourth graders make after receiving ordinary instruction on adding and subtracting decimal fractions. Based on empirical findings from past research, on theories of student learning, and on your own experience, you develop a rationale which predicts that a common error on “ragged” addition problems will be adding the wrong numerals. One of the reasons for this prediction is that students are likely to ignore the values of the digit positions and “line up” the numerals as they do with whole numbers. For instance, if they are asked to add 53.2 + .16, they are likely to answer either 5.48 or 54.8.

When you conduct your study, you present problems, handwritten, in both horizontal and vertical form. The horizontal form presents the numbers using the format shown above. The vertical form places one numeral over the other but not carefully aligned:

You find the predicted error occurs, but only for problems written in vertical form. To interpret these data, you look back at your theoretical framework and realize that students might ignore the value of the digits if the format reminded them of the way they lined up digits for whole number addition but might consider the value of the digits if they are forced to align the digits themselves, either by rewriting the problem or by just adding in their heads. A measure of what you (and others) learned from this study is the change in possible explanations (your theoretical frameworks). This does not mean your updated theoretical framework is “correct” or will make perfectly accurate predictions next time. But, it does mean that you are very likely moving toward more accurate predictions and toward a deeper understanding of how students think about adding decimal fractions.

Anchoring the Coherence of Your Study (and Your Evolving Research Paper)

Your theoretical framework serves as the anchor or center point around which all other aspects of your study should be aligned. This does not mean it is created first or that all other aspects are changed to align with the framework after it is created. The framework also changes as other aspects are considered. However, it is useful to always check alignment by beginning with the framework and asking whether other aspects are aligned and, if not, adjusting one or the other. This process of checking alignment is equally true when writing your evolving research paper as when planning and conducting your study.

Part III. How Do You Construct a Theoretical Framework for Your Study?

How do you start the process? Because constructing a theoretical framework is a natural extension of constructing rationales for your predictions, you already started as soon as you began formulating hypotheses: making predictions for what you will find and writing down reasons for why you are making these predictions. In Chap. 2 , we talked about beginning this process. In this section, we will explore how you can continue building out your rationales into a full-fledged theoretical framework.

Building a Theoretical Framework in Phases

Building your framework will occur in phases and proceed through cycles of clarifying your questions, making more precise and explicit your predictions, articulating reasons for making these predictions, and imagining ways of testing the predictions. The major source for ideas that will shape the framework is the research literature. That said, conversations with colleagues and other experts can help clarify your predictions and the rationales you develop to justify the predictions.

As you read relevant literature, you can ask: What have researchers found that help me predict what I will find? How have they explained their findings, and how might those explanations help me develop reasons for my predictions? Are there new ways to interpret past results so they better inform my predictions? Are there ways to look across previous results (and claims) and see new patterns that I can use to refine my predictions and enrich my rationales? How can theories that have credibility in the research community help me understand what I might find and help me explain why this is the case? As we have said, this process will go back and forth between clarifying your predictions, adjusting your rationales, reading, clarifying more, adjusting, reading, and so on.

One Researcher’s Experience Constructing a Theoretical Framework: The Continuing Case of Martha

In Chap. 2 , we followed Martha, a doctoral student in mathematics education, as she was working out the topic for her study, asking questions she wanted to answer, predicting the answers, and developing rationales for these predictions. Our story concluded with a research question, a sample set of predictions, and some reasons for Martha’s predictions. The question was: “Under what conditions do middle school teachers who lack conceptual knowledge of linear functions benefit from five 2-hour learning opportunity (LO) sessions that engage them in conceptual learning of linear functions as assessed by changes in their teaching toward a more conceptual emphasis of linear functions?” Her predictions focused on particular conditions that would affect the outcomes in particular ways. She was beginning to build rationales for these predictions by returning to the literature and identifying previous research and theory that were relevant. We continue the story here.

Imagine Martha continuing to read as she develops her theoretical framework—the rationales for her predictions. She tweaks some of her predictions based on what other researchers have already found. As she continues reading, she comes across some related literature on learning opportunities for teachers. A number of articles describe the potential of another form of LOs that might help teachers teach mathematics more conceptually—analyzing videos of mathematics lessons.

The data suggested that teachers can improve their teaching by analyzing videos of other teachers’ lessons as well as their own. However, the results were mixed so researchers did not seem to know exactly what makes the difference. Martha also read that teachers who already can analyze videos of lessons and spontaneously describe the mathematics that students are struggling with and offer useful suggestions for how to improve learning opportunities for students teach toward more conceptual learning goals, and their students learn more (Kersting et al., 2010 , 2012 ). These findings caught Martha’s attention because it is unusual to find correlates with conceptual teaching and better achievement. What is not known, realized Martha, is whether teachers who learn to analyze videos in this way, through specially designed LOs, would look like the teachers who already could analyze them. Would teachers who learned to analyze videos teach more conceptually?

It occurred to Martha she could bring these lines of research together by extending what is known along both lines. Recall our earlier suggestion of looking across the literature and noticing new patterns that can inform your work. Martha thought about studying how, exactly, these two skills are related: analyzing videos in particular ways and teaching conceptually. Would the relationships reported in the literature hold up for teachers who learn to describe the mathematics students are struggling with and make useful suggestions for improving students’ LOs?

Martha was now conflicted. She was well on her way to developing a testable hypothesis about the effects of learning about linear functions, but she was really intrigued by the work on analyzing videos of teaching. In addition, she saw several advantages of switching to this new topic:

The research question could be formulated quite easily. It would be something like: “What are the relationships between learning to analyze videos of mathematics teaching in particular ways (specified from prior research) and teaching for conceptual understanding?”

She could imagine predicting the answers to this question based directly on previous research. She would predict connections between particular kinds of analysis skills and levels of conceptual teaching of mathematics in ways that employed these skills.

The level of conceptual teaching, a challenging construct to define with her previous topic (the effects of professional development on the teaching of linear functions), was already defined in the work on analyzing videos of mathematics teaching, so that would solve a big problem. The definition foregrounded particular sets of behaviors and skills such as identifying key learning moments in a lesson and focusing on students’ thinking about the key mathematical idea during these moments. In other words, Martha saw ways to adapt a definition that had already been used and tested.

The issue of transfer—another challenging issue in her original hypothesis—was addressed more directly in this setting because the learning environment—analyzing videos of classroom teaching—is quite close to the classroom environment in which participants’ conceptual teaching would be observed.

Finally, the nature of learning opportunities, an aspect of her original idea she still needed to work through, had been explored in previous studies on this new topic, and connections were found between studying videos and changes in teaching.

Given all these advantages, Martha decided to change her topic and her research question. We applaud this decision for two major reasons. First, Martha’s interest grew as she explored this new topic. She became excited about conducting a study that might answer the research question she posed. It is always good to be passionate about what you study. Second, Martha was more likely to contribute important new insights if she could extend what is already known rather than explore a new area. Exploring something quite new requires lots of effort defining terms, creating measures, making new predictions, developing reasons for the predictions, and so on. Sometimes, exploring a new area has payoffs. But, as a beginning researcher, we suggest you take advantage of work that has already been done and extend it in creative ways.

Although Martha’s idea of extending previous work came with real advantages, she still faced a number of challenges. A first, major challenge was to decide whether she could build a rationale that would predict learning to analyze videos caused more conceptual teaching. Or, could she only build a rationale that would predict that there was a relationship between changes in analyzing videos and level of conceptual teaching? Perhaps a cause-effect relationship existed but in the opposite direction: If teachers learned to teach more conceptually, their analysis of teaching videos would improve. Although most of the literature described learning to analyze videos as the potential cause of teaching conceptually, Martha did not believe there was sufficient evidence to build a rationale for this prediction. Instead, she decided to first determine if a relationship existed and, if so, to understand the relationship. Then, if warranted, she could develop and test a hypothesis of causation in a future study. In fact, the direction of the causation might become clearer when she understood the relationship more clearly.

A second major challenge was whether to study the relationship as it existed or as one (or both) of the constructs was changing. Past research had explored the relationship as it existed, without inducing changes in either analyzing videos or teaching conceptually. So, Martha decided she could learn more about the relationship if one of the constructs was changing in a planned way. Because researchers had argued that teachers’ analysis of video could be changed with appropriate LOs, and because changing teachers’ teaching practices has resisted simple interventions, Martha decided to study the relationship as she facilitated changes in teachers’ analysis of videos. This would require gathering data on the relationship at more than one point in time.

Even after resolving these thorny issues, Martha faced many additional challenges. Should she predict a closer relationship between learning to analyze video and teaching for conceptual understanding before teachers began learning to analyze videos or after? Perhaps the relationship increases over time because conceptual teaching often changes slowly. Should she predict a closer relationship if the content of the videos teachers analyzed was the same as the content they would be teaching? Should she predict the relationship will be similar across pairs of similar topics? Should she predict that some analysis skills will show closer relationships to levels of conceptual teaching than others? These questions and others occurred to Martha as she was formulating her predictions, developing justifications for her predictions, and considering how she would test the predictions.

Based on her reading and discussions with colleagues, Martha phrased her initial predictions as follows:

There will be a significant positive correlation between teachers’ performance on analysis of videos and the extent to which they create conceptual learning opportunities for their students both before and after proposed learning experiences.

The relationship will be stronger:

Before the proposed opportunities to learn to analyze videos of teaching;

When the videos and the instruction are about similar mathematical topics; and,

When the videos analyzed display conceptual misunderstandings among students.

Of the video analysis skills that will be assessed, the two that will show the strongest relationship are spontaneously describing (1) the mathematics that students are struggling with and (2) useful suggestions for how to improve the conceptual learning opportunities for students.

Martha’s rationales for these predictions—her theoretical framework—evolved along with her predictions. We will not detail the framework here, but we will note that the rationale for the first prediction was based on findings from past research. In particular, the prediction is generated by reasoning that if there has been no special intervention, the tendency to analyze videos in particular ways and to teach conceptually develop together. This might explain Kersting’s findings described earlier. The second and third predictions were based on the literature on teachers’ learning, especially their learning from analyzing videos of teaching.

Before leaving Martha at this point in her journey, we want to make an important point about the change she made to her research topic. Changes like this occur quite often as researchers do the hard intellectual work of developing testable hypotheses that guide research studies. When this happens to you, it can feel like you have lost ground. You might feel like you wasted your time on the original topic. In Chap. 1 , we described inevitable “failure” when engaged in scientific inquiry. Failure is often associated with realizing the data you collected do not come close to supporting your predictions. But a common kind of failure occurs when researchers realize the direction they have been pursuing should change before they collect data. This happened in Martha’s case because she came across a topic that was more intriguing to her and because it helped solve some problems she was facing with the previous topic. This is an example of “failing productively” (see Chap. 1 ). Martha did not succeed in pursuing her original idea, but while she was recognizing the problems, she was also seeing new possibilities.

Constantly Improving Your Framework

We will use Martha’s experience to be more specific about the back-and-forth process in which you will engage as you flesh out your framework. We mentioned earlier your review of the literature as a major source of ideas and evidence that will affect your framework.

Reviewing Published Empirical Evidence

One of the best sources for helping you specify your predictions are studies that have been conducted on related topics. The closer to your topic, the more helpful will be the evidence for anticipating what you will find. Many beginning researchers worry they will locate a study just like the one they are planning. This (almost) never happens. Your study will be different in some ways, and a study that is very similar to yours can be extraordinarily helpful in specifying your predictions. Be excited instead of terrified when you come across a study with a title similar to yours.

Try to locate all the published research that has been conducted on your topic. What does “on your topic” mean? How widely should you cast your net? There are no rules here; you will need to use your professional judgment. However, here is a general guide: If the study does not help you clarify your predictions, change your confidence in them, or strengthen your rationale, then it falls outside your net.

In addition to helping specify your predictions, prior research studies can be a goldmine for developing and strengthening your theoretical framework. How did researchers justify their predictions or explain why they found what they did? How can you use these ideas to support (or change) your own predictions?

By reading research on similar topics, you might also imagine ways of testing your predictions. Maybe you learn of ways you could design your study, measures you could use to collect data, or strategies you could use to analyze your data. As you find helpful ideas, you will want to keep track of where you found these ideas so you can cite the appropriate sources as you write drafts of your evolving research paper.

Examining Theories

You will read a wide range of theories that provide insights into why things might work like they do. When the phenomena addressed by the theory are similar to those you will study, the associated theories can help you think through your own predictions and why you are making them. Returning to Martha’s situation, she could benefit from reading theories on adult learning, especially teacher learning, on transferring knowledge from one setting to another, on professional development for teachers, on the role of videos in learning, on the knowledge needed to teach conceptually, and so on.

Focusing on Variables and Mechanisms

As you review the literature and search for evidence and ideas that could strengthen your predictions and rationales, it is useful to keep your eyes on two components: the variables you will attend to and the mechanisms that might explain the relationships between the variables. Predictions could be considered statements about expected behaviors of the variables. The theoretical framework could be thought of as a description of all the variables that will be deliberately attended to plus the mechanisms conjectured to account for these relationships.